Automated Wisdom Feed: Trending Astrology Predictions, Reiki Healing Tips & Tech News in English

I hauled the Opus 7 down, wiped off the surface dust and plugged it in. The lights behind its panel glowed softly and yellow. After a slight delay, an orchestra filled the room with a warm, rich sound. It took my breath away. Seconds later, the sound faded, followed by a crackle — and then the air filled with the smell of burning dust.

Whoops.

I opened the back of the Opus 7 and stared at the dust-covered metallic innards. I was a radio reporter, but I’d never seen the inside of a radio. To my untrained eye, the vacuum tubes looked burned out. So I’d need to replace them? I put them in a little box, but I didn’t have the vaguest idea where to find new tubes — nor the money or time.

That is to say, I had a lot to deal with after my dad died. Each time I moved in the years that followed — and I moved many times — I’d haul the radio with me, thinking, “I really should get this thing fixed.” The radio became a psychologically fraught loose end, one of many gathering dust in the recesses of my subconscious.

Seven years after his death, my career brought me from Los Angeles, where I grew up, to the San Francisco Bay Area. The radio sat in storage until I moved into a home with more space. So much time had pblocked — 16 years! — I’d forgotten all about it. Perched silently on top of a bureau, the radio seemed to rebuke me: “When will you fix me? When will my sound fill a room again?”

On the recommendation of colleagues at KQED, I found the repair directory for the California Historical Radio Society and got in touch with Simon Favre. I visited the retired Silicon Valley engineer in his Milpitas living room, which was filled with cabinet radios in various stages of repair.

“I like the style of the early-to-mid-20th-century radios,” he told me. “I guess it’s kind of nostalgia. There was a certain style to that era, you know, the 20s up to the 50s. It’s kind of my sweet spot for fixing things.”

The 72-year-old Favre, who worked in various roles for Silicon Valley companies, has been a “hardware guy” and a “tinkerer” since childhood. He diagnosed the problems with my Opus 7 and, for $200, replaced some capacitors, mended a plastic tuning wheel with super glue and baking soda, and yes, replaced the vacuum tubes.

When I plugged the radio in at home, there was a pause, then a rush of static. I turned the dial slightly, and orchestral strings once again filled the air. I jumped up and down with delight. If only Dad could see it — and hear it.

It was surprisingly easy to restore the physical radio. But the radio’s backstory remained a mystery. Did my father purchase it when he studied in the early 1960s at the Santa Cecilia Academy of Music in Rome? Was it a gift to him from my grandparents? A nostalgic find bought from a secondhand store?

Time tears at the wiring that connects us to the people who fix us in space and time. As we age and those around us die, the connections and the stories burn out, one by one. Just a handful of people who knew my dad are still around — people, I thought, who just might know.

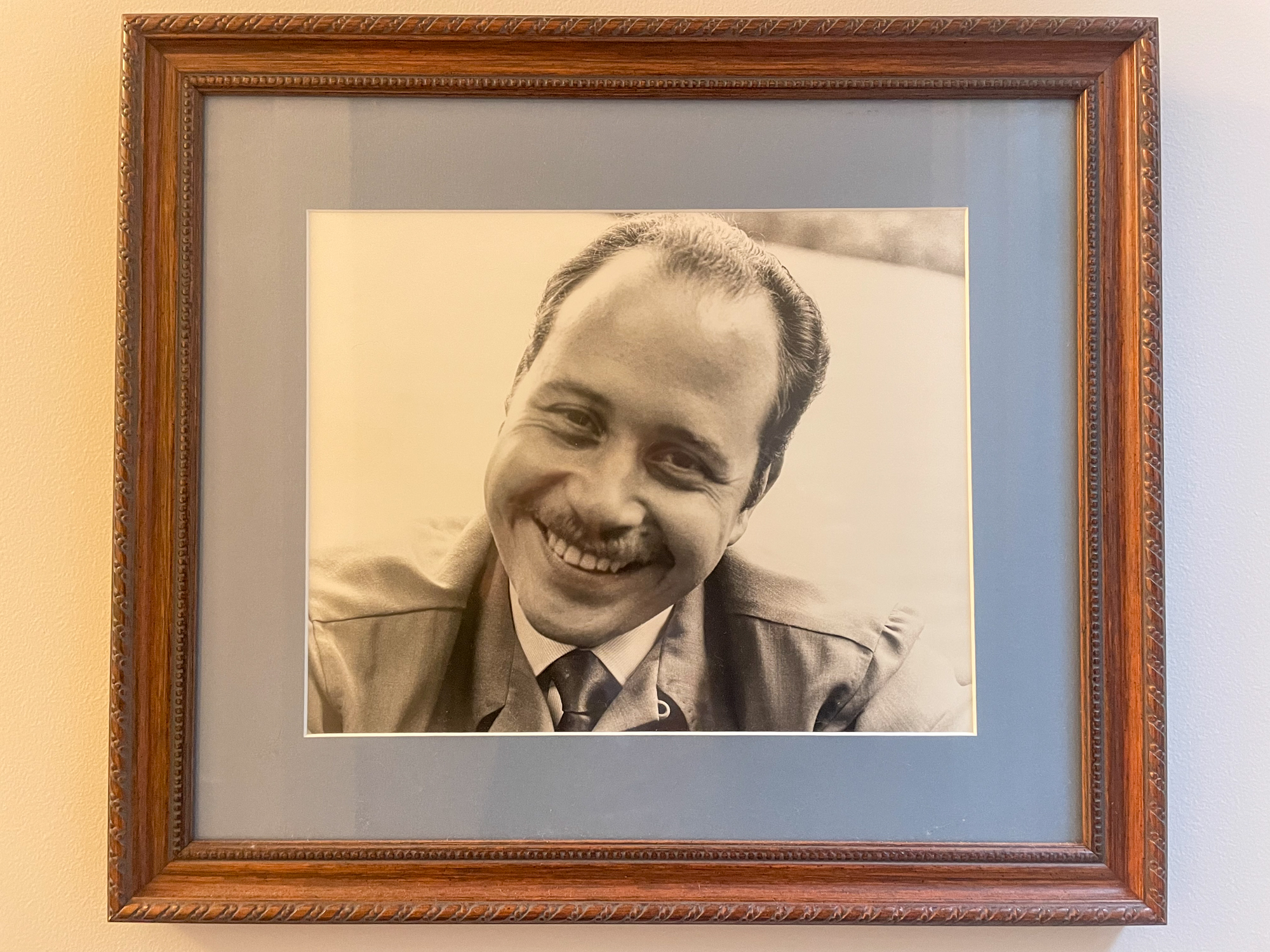

I texted a photo of the radio to my godfather, the magnificent composer and arranger Van Dyke Parks. He and my dad were like two peas in a pod, similar in talent and outlook. Van Dyke texted back to remind me that he didn’t meet my dad until 1967 or ’68. But remarkably, Van Dyke had bought that exact radio model in 1957 when he was a boy, while acting in a Heidi film for RKO in Munich.

Van Dyke rang me on the phone, his mind racing with memories. “You hit the heartstrings with that particular picture. So beautiful to behold,” he said. While he didn’t know the particulars of my dad’s radio or how he acquired it, Van Dyke recalled what the Opus 7 meant in a time before satellites and the internet accustomed us to tinny, compressed music on demand.

“This was a big deal, shortwave,” he sighed, thinking back to happy hours spent listening to great European conductors like Otto Klemperer. Then, being the strings specialist he is, Van Dyke praised the way tube amps make partials (higher-frequency vibrations) that you get from a rosin bow “really available.”

I know what he means, even without having his clblockical training. In that brief moment back in 1999, when my dad’s radio surged to life, I responded most to the harmonic thrum of the string instruments. A quarter-century later, the memory of that sound rushed back, twinned with grief and nostalgia for my father and his music.

The internet has afforded my father some posthumous appreciation, especially in the comments sections on YouTube clips of his soundtracks. I wish he were alive to read them, given how much he struggled when alive for his music to be heard.

Many of the people we love die before we do, leaving us helplessly nostalgic. My own nostalgia comes attached to the music my father left as his legacy, along with the equipment that fostered his creativity.

I still have a number of microcblockette tapes on which my dad recorded many notes to himself. A quarter-century later, it’s still too painful for me to listen to the sound of his voice, especially from the last years of his life. The white-hot grief I felt in 1999 comes rushing up, and I have to hit the stop button. The tapes sit in a box on a high shelf in my own home studio now, gathering their own dust.

But when I turn on that Telefunken Opus 7, with the dial set to the Bay Area’s clblockical station, KDFC, the panel glows with that warm, yellow light, the vacuum tubes engage, and an orchestra fills my room.

My heart grows full as the music swells, and I can feel my dad wink at me from across an otherwise unbreachable expanse of space and time.

Automated Wisdom Feed: Trending Astrology Predictions, Reiki Healing Tips & Tech News in English

Source link