Automated Wisdom Feed: Trending Astrology Predictions, Reiki Healing Tips & Tech News in English

And nobody knows how many are out there.

“It is entirely possible that we have a million or more undo***ented wells in the United States,” says Mary Kang, an ***ociate professor at McGill University who has extensively researched methane emissions from these old wells.

This old problem is attracting new scrutiny, and a multibillion dollar effort to fix it.

Step one: Figuring out where they are.

Hunting for orphans

Last spring, Dan Arthur, a petroleum engineer and geologist, stepped carefully through Oklahoma prairie gr***es to examine a capped pipe sticking out of the ground. An entourage followed: Arthur’s stepson, an NPR reporter, a photographer, and one of Arthur’s employees with an expensive camera that could detect gas leaks.

Arthur’s an oil guy. He loves the view of pumpjacks scattered over the prairie, the oil pumps that bob up and down across the horizon like strange, skinny birds pecking at the ground in slow motion. But to him, orphan wells are a serious problem — and they’re a lot less visible than those pumpjacks. “A lot of people don’t see them,” Arthur says with frustration.

And if you don’t see them, you don’t even know there’s a problem there to fix.

Finding them is kind of like hunting for fossils, another hobby of Arthur’s. “Some people take their friends fishing,” he said, standing in Tallgr*** Prairie Preserve in Osage County and gazing out on a stormy horizon. “I’ll go, ‘Let’s go hunt for dinosaurs.’ You know, ‘Let’s go hunt for orphan wells.’”

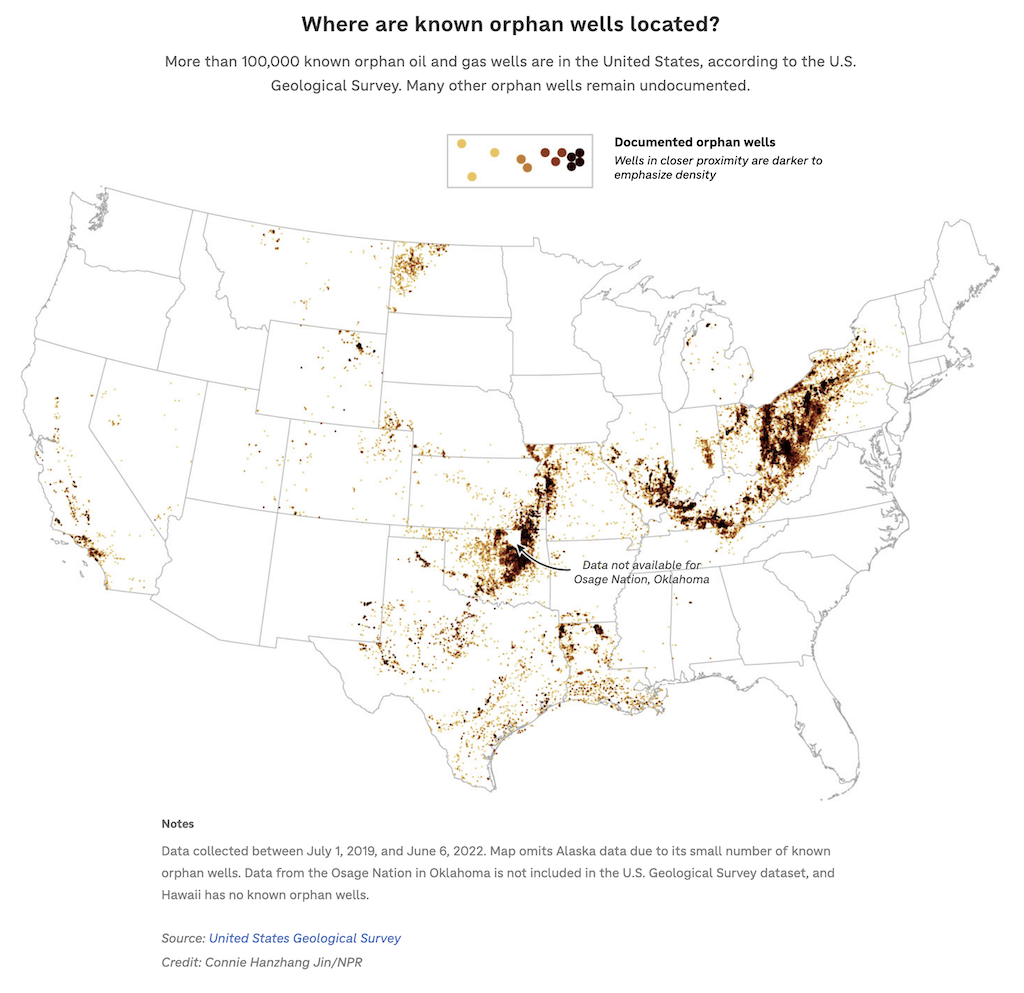

More than 100,000 orphan wells have been do***ented, but everyone in the industry knows the problem is much bigger than that. Arthur and his stepsons have found wells in the middle of the Arkansas River in Tulsa, actively leaking pollutants into the river. They’ve found old wells in urban parks.

Some orphan wells were drilled and abandoned in the early days of the oil industry, before modern techniques for plugging defunct wells were developed, let alone required. And that helps explain why they’d be missing from maps.

Or, as Arthur put it, with exaggerated skepticism: “You think all these early wells in Osage, when they were drilling, had permits?”

The history of oil development in Osage Nation is long and violent. A hundred years ago, as oil boomed, white people murdered many members of the tribe to steal their oil wealth — maybe you saw Killers of the Flower Moon.

A few of the wells drilled during that bloody string of murders are still pumping today. Others are relics, left unplugged.

This problem spans the nation. There were early oil booms in Appalachia, California and Texas, and they too left a legacy of unplugged, undo***ented wells.

Most people don’t look for these wells on spring break, like Arthur and his stepsons — but lots of groups are hunting for them. The Department of Energy is working with state regulators and tribal groups (including the Osage Nation), as well as academics and advocacy groups to map more orphan wells.

That means looking at historical photos, applying machine learning to old oil records, attaching magnetometers to drones, using aerial photography, and, of course, going out into the field to look in person.

“We’re finding more and more every single day,” says Craig Walker, of the Department of Natural Resources for the Osage Nation.

It’s unplugged. But is it orphaned?

Not all orphan wells are old — and putting a pin in a map isn’t always the end of the story.

Take the waist-high, capped pipe that Arthur was examining, surrounded by pristine prairie and bison dung. Arthur said it could be an orphan well — “We don’t really know.”

It definitely wasn’t drilled a century ago. It was, in fact, drilled in recent memory.

“That was one of my favorites,” says Shane Matson, the geologist and former oilman who drilled the now-idled well in the early 2010s. “It was a spectacular, very fascinating well.”

But, thanks in part to a market crash, the well was never profitable to run. Matson sold the well to a former business partner a decade ago. Then that partner sold it, too, Matson says.

So who’s responsible for plugging the well? The Osage Nation’s records indicate the well is potentially orphaned, and may be investigated to determine whether it should be formally categorized as such. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, which administers the oil and gas leases in Osage County, maintains Matson’s company is still responsible for plugging it. Matson says that company was bought by another, along with all of its ***ets, and doesn’t even exist as its own entity any more.

It’s not an unusual situation. In many cases, responsibility for orphan wells gets p***ed along like a hot potato.

That’s because an unprofitable well is very expensive to close properly. It’s much cheaper to put a small cap on top as a short-term solution.

Such a well — capped, but not permanently plugged — can be sold from one company to another. That can end two ways: A company, usually under pressure from regulators, finally agrees to plug the well. Or it goes bankrupt and the well is orphaned. Now, plugging it is up to the government.

And there’s another wrinkle. Before actually plugging an orphan well, the Osage would also need to confirm that the well wouldn’t be better off being reopened as a source of oil.

Automated Wisdom Feed: Trending Astrology Predictions, Reiki Healing Tips & Tech News in English

Source link