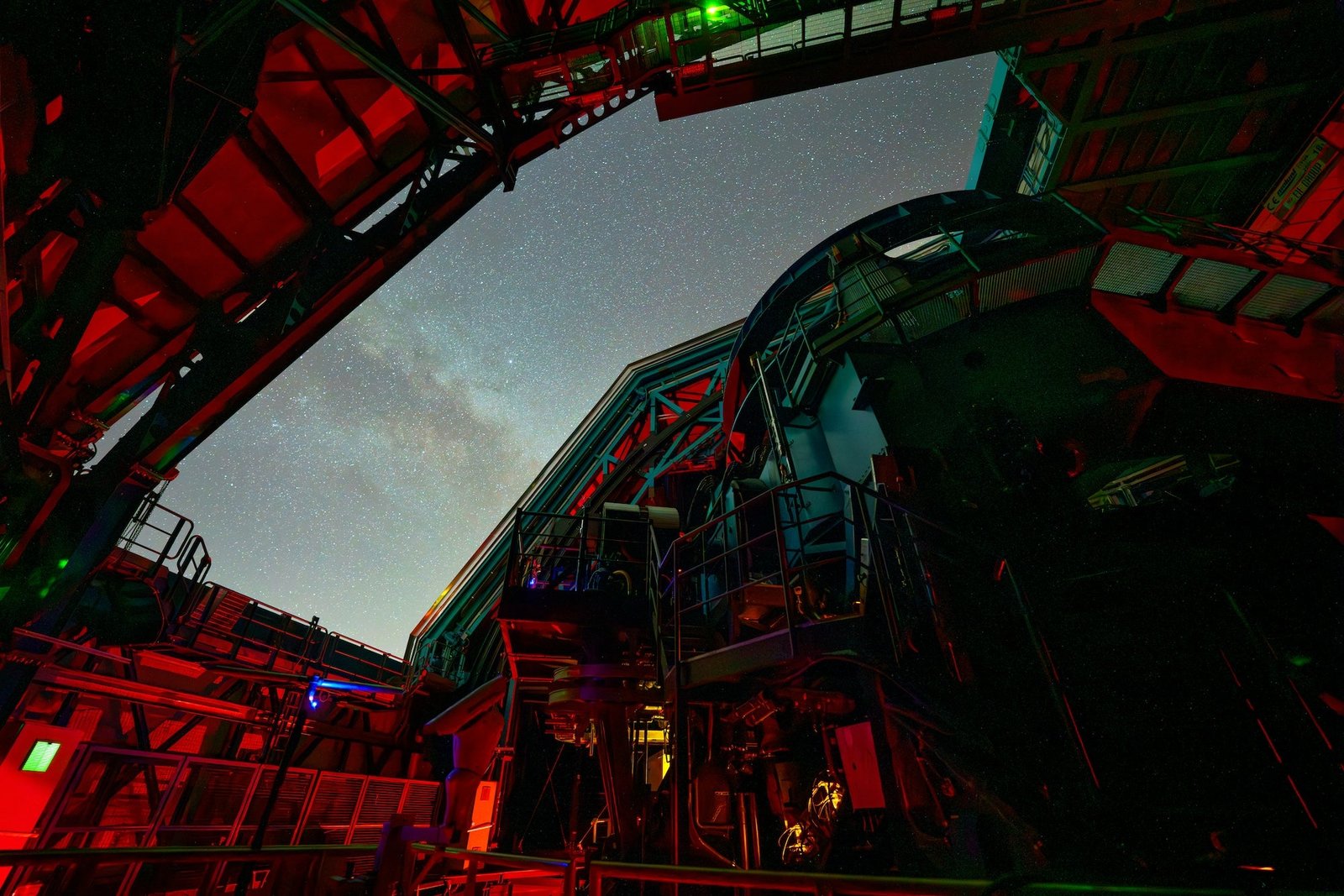

The Simonyi Survey Telescope peers at the sky from inside the dome of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Credit: NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory/H. Stockebrand

It’s been an exciting morning, with the initial release of images from the The National Science Foundation–U.S. Department of Energy Vera C. Rubin Observatory. But these were just the first taste — a press conference this morning unveiled more images as well as videos to the world.

“This observatory represents a giant leap in our ability to explore the cosmos and unwrap the mysteries of the universe,” said Kathy Turner, U.S. DOE Program Manager for Rubin Observatory, during the press conference.

In addition to its ultra-wide field of view (9.62 square degrees), Rubin Observatory’s 8.4-meter Simonyi Survey Telescope and 3,200-megapixel LSST Camera can snap successive images and move on to a new area of the sky quickly as part of the planned Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), which will begin later this year. That sets the stage for the telescope’s other exciting capability: creating time-stepped “movies” of the entire Southern Hemisphere sky for the next 10 years as part of the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

Why movies? “The sky is not static — it’s alive,” said Yusra AlSayyad, who manages the observatory’s image-processing algorithms, in a press release last month. Those algorithms allow the observatory to detect changes and issue alerts within seven seconds after each image is taken, resulting in millions of detections for astronomers to follow up on… per night.

New asteroids

Showing off that capability this morning is a video highlighting some of the thousands (yes, thousands!) of asteroids the observatory has already discovered just in this initial phase. Asteroids are notoriously difficult to spot, as they’re small (and thus faint) and are only detectable through their motion through the sky. That means a telescope needs to be taking many images of the same patch of sky over time to notice any foreground object that moves.

And that is exactly what Rubin will do.

This video shows new asteroids discovered by Rubin Observatory in a span of just 10 hours. In this short time, Not only does the image show the two-dimensional paths of the asteroids across image frames, but it also shows the new asteroids’ 3D positions in space within the solar system.

Rubin caught sight of 2,104 previously unknown asteroids, seven of which are considered near-Earth objects whose orbits bring them to within some 28 million miles (45 million kilometers) of Earth. (Don’t worry, astronomers have determined that none of these will pose a hazard to our planet.) As of Monday morning, the discoveries have been reported to the Minor Planet Center at Harvard, said Rubin Observatory Director Zeljko Ivezic during the Monday press conference. He added, with regard to any object that might be found in the future that could be potentially hazardous: “As soon as we have a plausible discovery … within, sometimes even with less than 24 hours, everyone in the world will know that there is a potential object that could be hazardous. And they can get more data … [to] rule out the level of the danger. … Everyone in the world will be able to follow up on Rubin’s discoveries.”

Within one year, the LSST will likely discover more asteroids than all those found by other telescopes combined. Within two years, the number of new asteroids is expected to reach into the millions. And some of these won’t be native to our own solar system, but interstellar interlopers like 1I/2017 U1 ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov. The observatory might discover 10 or 20 of these during the LSST, Ivezic said.

He also noted that “If Planet Nine exists … Rubin is the best positioned observatory to discover it.”

Stepping through time

While many astronomical process take millions or billions of years to occur, some effect changes over minutes, hours, days, or weeks. Some variable stars, such as RR Lyrae stars, can briefly brighten within minutes or hours. Rubin’s sharp eye and sophisticated data blockysis algorithms can catch these stars pulsating at distances previously unreachable by other observing programs, creating a three-dimensional map of these stars throughout our galaxy and helping astronomers study the distribution of dark matter in the Milky Way.

And then there are sporadic one-time events, such as stars exploding or black holes swallowing a meal, which can light the night without warning for only a brief time before fading away. With telescope time so precious, astronomers must often balance the need for the long exposures in one location required to view faint or faraway objects with regularly scanning the sky to serendipitously catch new events. Of course, both of these goals are achievable with the Rubin Observatory’s technology and through the very design of the LSST.

And building up a 10-year record of the sky means that “if something strange appears — an explosion, an object vanishing — we can rewind and see what led up to it,” AlSayyad said in the release. All changes in the sky each night will be published within a day, and catalogs will be released yearly. Any part of the sky that might be of interest — and any time that part of the sky was imaged — will be readily available to astronomers, allowing them to step through the time before, during, and after any detected event for a detailed look.

“Once you’ve got the deep image, you go back to every single frame,” said Eli Rykoff, who is in charge of calibrating the images the observatory takes, in the release. “Then you ask: ‘What was the light like at this spot, at this moment?’ By repeating this process for all images, we can reconstruct light curves and track the evolution of an object’s brightness over time.”

Flying through space

But let’s not forget that ultra-wide field of view Rubin has, looking at a portion of the sky more than nine square degrees in a single shot. While the first images released showed only small portions — roughly 2 percent — of a larger image of the vast Virgo Cluster of galaxies, this new video gives a much better sense of just how immense the telescope’s field of view truly is, and how much of the cosmos it can capture in a single glimpse.

“The entire Rubin team is so excited about this data. We have been talking about this data for over two decades. It’s finally here,” Ivezic said during the press conference as the video was unveiled.

The video of the Virgo Cluster field comprises more than 1,100 images and takes us on a journey that starts with just two galaxies. But then it begins to move, pulling back and zooming around and around, uncovering colorful new galaxies at each turn. The video ultimately reveals a field of view 100 times as large as the small portions made available earlier today, with every bit of the view awash in galaxies — some 10 million in total. That’s just 0.05 percent of the 20 billion galaxies (containing a total of some 18 billion stars) Rubin is expected to observe by the end of its 10-year survey.

If you want to view and zoom around this image, Rubin’s web display tool is available at and offers both a guided view or the ability to explore the image on your own, bit by bit. The app also offers sonification, allowing you to explore not only the visual landscape with your eyes but also listen in on the cosmic “soundscape” with your ears.

Cataloging so many galaxies will allow astronomers to answer questions that range from how galaxies interact and evolve to how clumps and clusters of galaxies are spread throughout the universe. That latter point is related to fundamental properties of our cosmos, including the elusive dark matter and dark energy that dominate it. So, Rubin will not only take pretty pictures and make movies of the sky, it will show us the very makeup of our universe in ultra-high-def and help astronomers answer some of the most fundamental questions there are about why our universe is the way it is and where it might be headed.

“We believe the work of this observatory will help us find long-sought answers and ask new and better questions. It will also provide the best map mankind has yet made of our region of the universe,” said Michael Kratsios, Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Many of those questions will be about things we haven’t even discovered yet, or perhaps have seen only once or twice before in the history of astronomy. “When you’re talking [about] a survey where everything is on the scale of billions, those one-in-a-million events aren’t that rare anymore,” said Claire Higgs, Astronomy Outreach Specialist for the Rubin Observatory. “You get lots of one-in-a-million events if you’re talking on the scale of billions.”

Rubin is now poised to utterly transform our view of the cosmos in nearly countless ways. The journey is just getting started — so stay tuned.