Summer will officially arrive on Friday in what is known as the Summer Solstice.

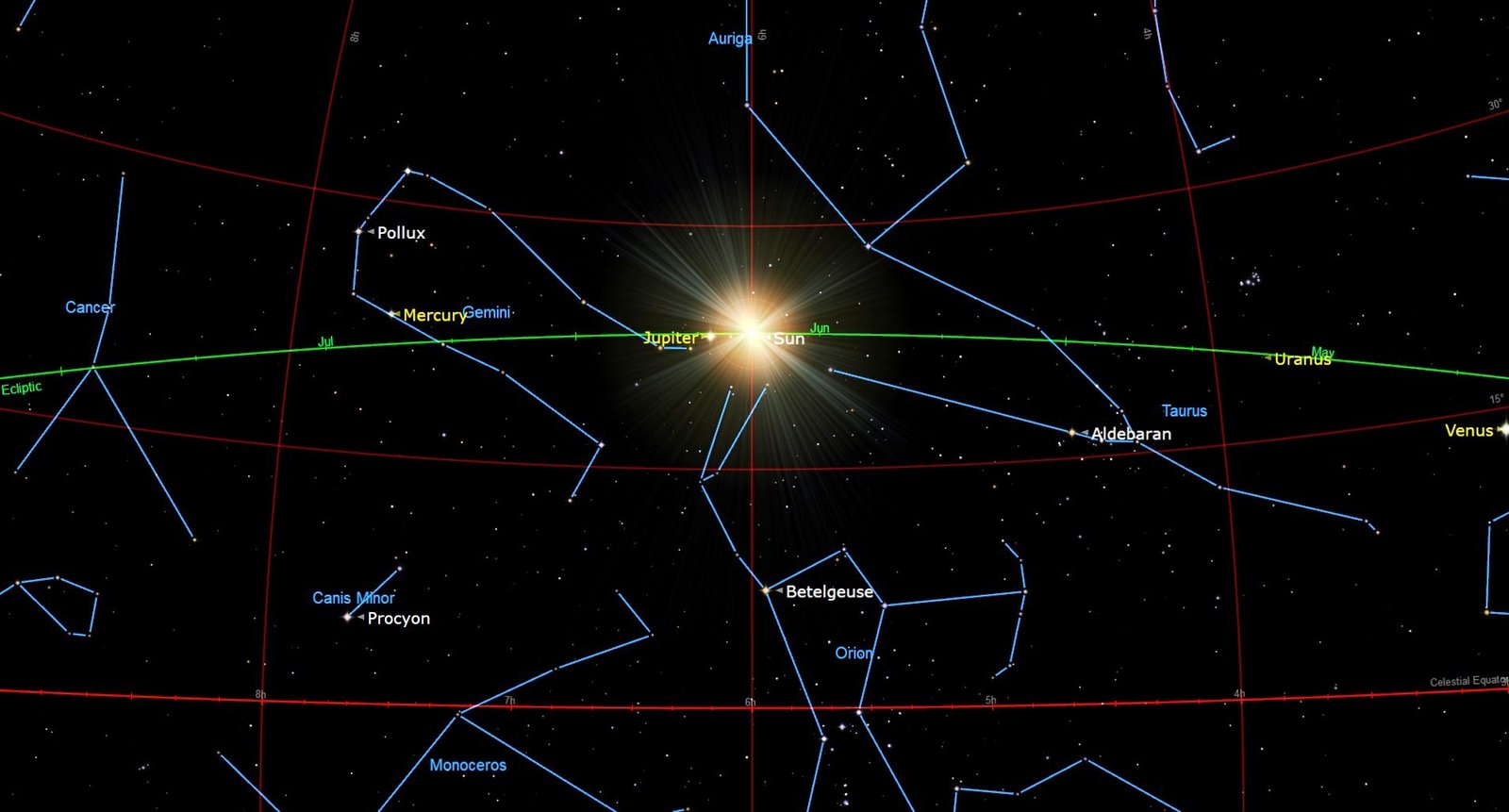

At 10:42 p.m. EDT on June 20 (0242 GMT on June 21), the sun will reach that point where it is farthest north of the celestial equator. To be more precise, when the solstice occurs the sun will appear to be shining directly overhead for a point on the Tropic of Cancer (latitude 23.5 degrees north) in the western Pacific Ocean, roughly 1,400 statute miles (890 km) to the south of Tokyo, Japan.

From mid-northern latitudes, we can never see the sun directly overhead, but (as an example) as seen from Philadelphia at 1:02 p.m. EDT on the day of the summer solstice, the sun will attain its highest point in the sky for this entire year, standing 73 degrees above the southern horizon. To gauge how high that is, your clenched fist held at arm’s length measures roughly 10 degrees, so from “The City of Brotherly Love,” the sun will appear to climb more than “seven fists” above the southern horizon. And since the sun will appear to describe such a high arc across the sky, the duration of daylight will be at its most extreme, lasting exactly 15 hours.

Twilight zones

But this doesn’t mean that we can stargaze for the 9 hours remaining because we also need to take twilight into consideration. Around the time of the June solstice at latitude 40 degrees north, morning and evening twilight each last just over 2 hours, so the sky is fully dark for only 5 hours.

Farther north, twilight lasts even longer. At 45 degrees it lingers for 2.5 hours and at 50 degrees twilight persists through the entire night; the sky never gets completely dark. In contrast, heading south, the duration of twilight is shorter. At latitude 30 degrees it lasts 96 minutes while at the latitude of San Juan it only lingers for 80 minutes. Which is why travelers from the northern U.S. who visit the Caribbean at this time of year are so surprised at how quickly it gets dark after sunset compared to back home.

Incidentally, the earliest sunrise and latest sunset do not coincide with the summer solstice. The former occurred on June 14, while the latter does not come until June 27.

So far, so good

Most people are probably under the impression that the Earth is closest to the sun in its orbit at this time of year, but actually, it is just the opposite. In fact, on July 3, at 19:55 Universal Time or 3:55 p.m. Eastern daylight time, we’ll be at that point in our orbit farthest from the sun (called aphelion); a distance of 94,502,939 miles (152,087,738 km).

Conversely, it was back on Jan. 4 that Earth was at perihelion, its closest point to the sun. The difference in distance between these two extremes measures 3,096,946 miles (4,984,051 km) or 3.277 percent, which makes a difference in radiant heat received by the Earth of nearly 7 percent. Thus, for the Northern Hemisphere the difference tends to warm our winters and cool our summers.

However, in reality, the preponderance of large landm***es in the Northern Hemisphere works the other way and overall tends to make our winters colder and summers hotter than those of the Southern Hemisphere.

After Aug. 6 it “gets late early”

After the sun arrives at its solstice point, it will begin to migrate back toward the south and the amount of daylight in the Northern Hemisphere will begin to decrease. Consider this: after Friday, the length of daylight will not begin to increase again until three days before Christmas. But actually, if you think about it, the sun has been taking a high arc across the sky and the length of daylight has been rather substantial since about the middle of May. And the lowering of the sun’s path in the sky and the diminishing of the daylight hours in the coming days and weeks will, at least initially, be rather subtle.

Aug. 1 is marked on some Christian calendars as Lammas Day, whose name is derived from the Old English “loaf-m***,” because it was once observed as a harvest festival and was traditionally considered to be the middle of the summer season. In actuality, however, summer’s midpoint — that moment that comes exactly between the summer solstice and the autumnal equinox in 2024 — will not occur until Aug. 6 at 6:30 p.m. EDT. On that day, again, as seen from Philly, the sun will set at 8:08 p.m. with the loss of daylight since June 20 amounting to just 56 minutes.

But it is in the second half of summer that the effects of the southward shift of the sun’s direct rays start becoming much more noticeable. In fact, when autumn officially arrives on Sept. 22, the sun for Philadelphians will be setting a few minutes before seven in the evening (6:57 p.m.), while the length of daylight will have been reduced by nearly two hours (1 hour 55 minutes to be precise) since Aug. 6.

When he occasionally played left field during his Hall of Fame career with the Yankees, Yogi Berra would say that he didn’t mind the outfield, except that during August and September, as the shadows across the ballfield progressively lengthened, it made it increasingly difficult for him to see a baseball hit in his direction.

Yogi might not have been able to explain the science of why the altitude of the sun lowered so perceptibly during the latter half of the summer, but — as only Yogi could do — he was able to sum it all up in a simple Yogism:

“It’s getting late early out there.”

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.