Noted sand-hater Anakin Skywalker may want to cross the planetary system of YSES-1 off his list of potential summer vacation locations.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have discovered a planetary system orbiting a youthful star located 300 light-years away. The system’s two planets, YSES-1 b and YSES-1 c, are packed with coarse, rough, and frankly irritating silica material (we get you, Anakin, it does get everywhere).

Astronomers say this discovery around a star that is just 16.7 million years old could hint at how the planets and moons of our 4.6 billion-year-old solar system took shape. As both planets are gas giants, they could offer astronomers an opportunity to study the real-time evolution of planets like Jupiter and Saturn.

“Observing silicate clouds, which are essentially sand clouds, in the atmospheres of extrasolar planets is important because it helps us better understand how atmospheric processes work and how planets form, a topic that is still under discussion since there is no agreement on the different models,” team member Valentina D’Orazi of the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) said in a statement. “The discovery of these sand clouds, which remain aloft thanks to a cycle of sublimation and condensation similar to that of water on Earth, reveals complex mechanisms of transport and formation in the atmosphere.

“This allows us to improve our models of climate and chemical processes in environments very different from those of the solar system, thus expanding our knowledge of these systems.”

Building a ‘sandcastle’ world

One of these extrasolar planets, or “exoplanets,” YSES-1 c, has a mass around 14 times the mass of Jupiter. On YSES-1 c, this silica matter is located in clouds in its atmosphere, which gives it a reddish hue and creates sandy rains that fall inward towards its core.

We guess that the future Darth Vader didn’t build too many sandcastles in his youth, but that process is analogous to the formation of sandy matter that YSES-1 b is undergoing.

Already possessing a mass around six times that of Jupiter, the still-forming sandcastle planet YSES-1 b is surrounded by a flattened cloud or “circumplanetary disk” that is supplying it with building materials, including silicates.

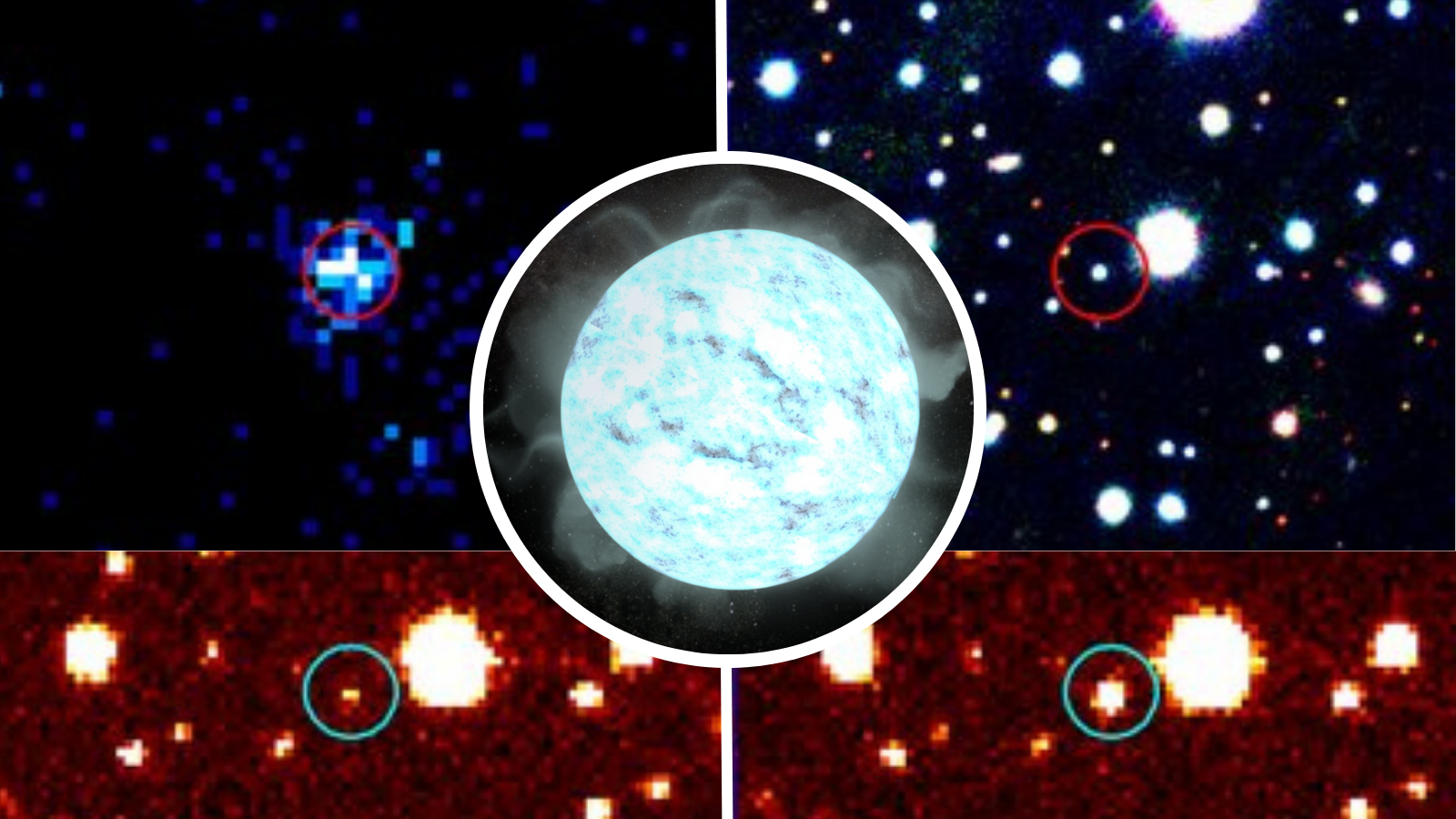

Not only is this the first direct observation of silica clouds (specifically iron-rich pyroxene or a combination of bridgmanite and forsterite) high in the atmosphere of an exoplanet, but it is also the first time silicates have been detected in a circumplanetary disk.

The JWST was able to make such detailed direct observations of both planets thanks to the great distances at which they orbit their parent star, which is equivalent to between 5 and 10 times the distance between the sun and its most distant planet, the ice giant Neptune.

Though this technique is still restricted to a small number of planets beyond the solar system, this research exemplifies the capability of the JWST to provide high-quality spectral data for exoplanets. This opens the possibility of studying both the atmospheres and circumplanetary environments of exoplanets in far greater detail.

“By studying these planets, we can better understand how planets form in general, a bit like peering into the past of our solar system,” added D’Orazi. “The results support the idea that cloud compositions in young exoplanets and circumplanetary disks play a crucial role in determining atmospheric chemical composition.

“Furthermore, this study highlights the need for detailed atmospheric models to interpret the high-quality observational data obtained with telescopes such as JWST.”

The team’s results were published on Tuesday (June 10) in the journal Nature, the same day as they were presented at the 246th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Anchorage, Alaska.