The cranial nerves (blue) and blood vessels (red) in the head of a mouse are revealed by a high-resolution imaging technique. Credit: M.-Y. Shi et al./Cell (CC-BY-4.0)

A speedy imaging method can map the nerves running from a mouse’s brain and spinal cord to the rest of its body at micrometre-scale resolution, revealing details such as individual fibres travelling from a key nerve to distant organs1.

Previous efforts have mapped the network of connections between nerve cells, known as the connectome, in the mouse brain. But tracing the complex paths of nerves through the rest of the body has been challenging. To do so, the creators of the new map used a custom-built microscope to scan exposed tissue, completing the process in just 40 hours.

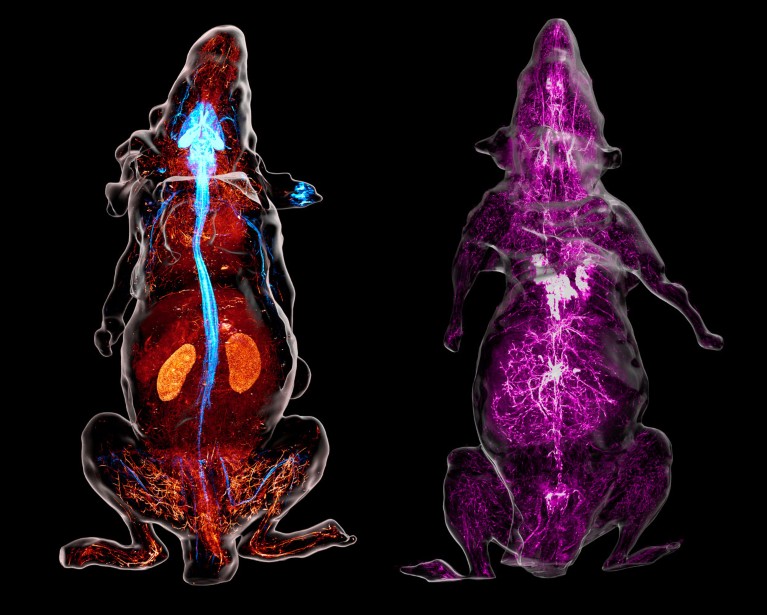

Nerves look blue in the reconstructed view of a genetically engineered mouse (left) whose neurons produce a fluorescent marker. In a separate animal (right), antibodies detail the sympathetic nerves (purple). Credit: M.-Y. Shi et al./Cell (CC-BY-4.0)

The method, described today in Cell, is an important technical achievement, says Ann-Shyn Chiang, a neuroscientist at the National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu, Taiwan, who was not involved with the research. “This work is a major step forward in expanding connectomics beyond the brain,” he says.

Clearing the way

To prepare a mouse’s body for the scan, researchers treat it with chemicals that make its tissues transparent by removing fat, calcium and other components that block light. This provides a clear view of the nerves, which have been labelled with fluorescent marker proteins. The see-through body is then placed into a device that combines a slicing tool and a microscope that takes 3D images.

A piston gradually pushes the mouse towards the slicing blade, 400 micrometres at a time. After each slice, a microscope images the newly exposed surface of the mouse, capturing details up to 600 micrometres deep — roughly the thickness of six sheets of paper — below the surface. The body then advances for the next cut. The cycle repeats around 200 times without pause, to cover the entire body. The images are then combined.

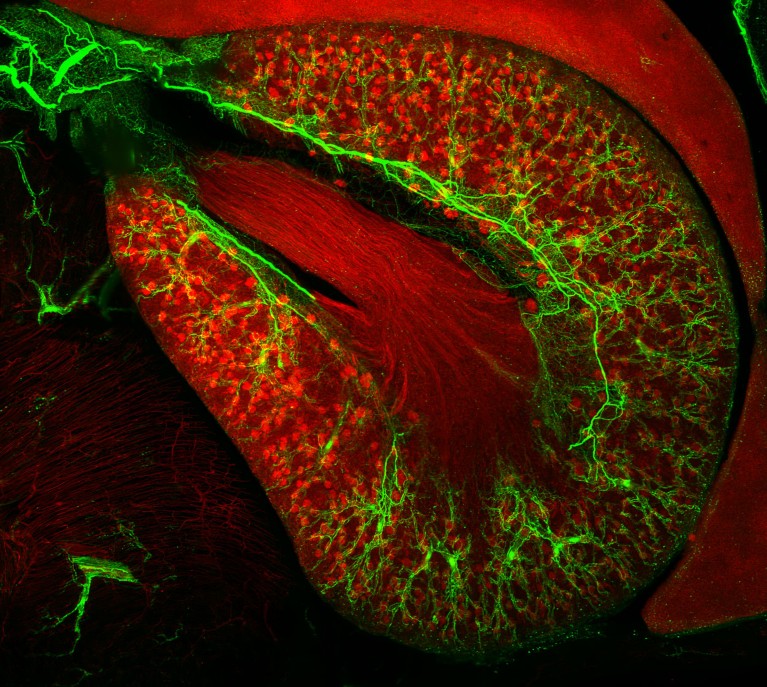

Sympathetic nerves (green) can be seen branching through the outer layer of the kidney thanks to antibody labelling of proteins in nerve cells. Credit: M.-Y. Shi et al./Cell (CC-BY-4.0)

The authors say the method is much faster than other techniques, which require frequent pauses. “A slower system would take months or years, increasing the chance of mechanical failure, signal loss or sample degradation,” says co-author Guoqiang Bi, a neuroscientist at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei.

Mouse with a glow

Researchers repeated the process on 16 adult mice, using three distinct marking techniques to label subsets of nerves.