Could Iran Have Been Close to Making a Nuclear Weapon? Uranium Enrichment Explained

When Israeli aircraft recently struck a uranium-enrichment complex in the nation, Iran could have been days away from achieving “breakout,” the ability to quickly turn “yellowcake” uranium into bomb-grade fuel, with its new high-speed centrifuges

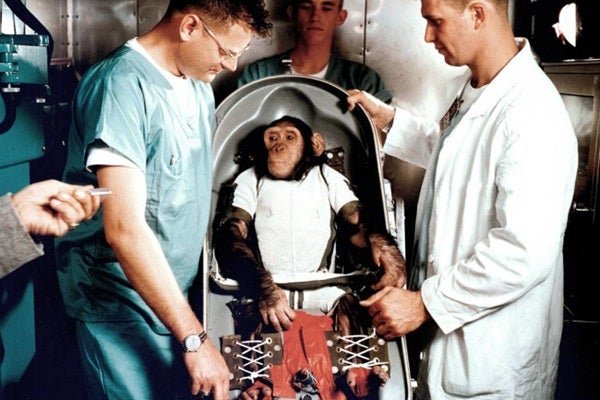

Men work inside of a uranium conversion facility just outside the city of Isfahan, Iran, on March 30, 2005. The facility in Isfahan made hexaflouride gas, which was then enriched by feeding it into centrifuges at a facility in Natanz, Iran.

In the predawn darkness on Friday local time, Israeli military aircraft struck one of Iran’s uranium-enrichment complexes near the city of Natanz. The warheads aimed to do more than shatter concrete; they were meant to buy time, according to news reports. For months, Iran had seemed to be edging ever closer to “breakout,” the point at which its growing stockpile of partially enriched uranium could be converted into fuel for a nuclear bomb. (Iran has denied that it has been pursuing nuclear weapons development.)

But why did the strike occur now? One consideration could involve the way enrichment complexes work. Natural uranium is composed almost entirely of uranium 238, or U-238, an isotope that is relatively “heavy” (meaning it has more neutrons in its nucleus). Only about 0.7 percent is uranium 235 (U-235), a lighter isotope that is capable of sustaining a nuclear chain reaction. That means that in natural uranium, only seven atoms in 1,000 are the lighter, fission-ready U-235; “enrichment” simply means raising the percentage of U-235.

U-235 can be used in warheads because its nucleus can easily be split. The International Atomic Energy Agency uses 25 kilograms of contained U-235 as the benchmark amount deemed sufficient for a first-generation implosion bomb. In such a weapon, the U-235 is surrounded by conventional explosives that, when detonated, compress the isotope. A separate device releases a neutron stream. (Neutrons are the neutral subatomic particle in an atom’s nucleus that adds to their m***.) Each time a neutron strikes a U-235 atom, the atom fissions; it divides and spits out, on average, two or three fresh neutrons—plus a burst of energy in the form of heat and gamma radiation. And the emitted neutrons in turn strike other U-235 nuclei, creating a self-sustaining chain reaction among the U-235 atoms that have been packed together into a critical m***. The result is a nuclear explosion. By contrast, the more common isotope, U-238, usually absorbs slow neutrons without splitting and cannot drive such a devastating chain reaction.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To enrich uranium so that it contains enough U-235, the “yellowcake” uranium powder that comes out of a mine must go through a lengthy process of conversions to transform it from a solid into the gas uranium hexafluoride. First, a series of chemical processes refine the uranium and then, at high temperatures, each uranium atom is bound to six fluorine atoms. The result, uranium hexafluoride, is unusual: below 56 degrees Celsius (132.8 degrees Fahrenheit) it is a white, waxy solid, but just above that temperature, it sublimates into a dense, invisible gas.

During enrichment, this uranium hexafluoride is loaded into a centrifuge: a metal cylinder that spins at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute—faster than the blades of a jet engine. As the heavier U-238 molecules drift toward the cylinder wall, the lighter U-235 molecules remain closer to the center and are siphoned off. This new, slightly U-235-richer gas is then put into the next centrifuge. The process is repeated 10 to 20 times as ever more enriched gas is sent through a series of centrifuges.

Enrichment is a slow process, but the Iranian government has been working on this for years and already holds roughly 400 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent U-235. This falls short of the 90 percent required for nuclear weapons. But whereas Iran’s first-generation IR-1 centrifuges whirl at about 63,000 revolutions per minute and do relatively modest work, its newer IR-6 models, built from high-strength carbon fiber, spin faster and produce enriched uranium far more quickly.

Iran has been installing thousands of these units, especially at Fordow, an underground enrichment facility built beneath 80 to 90 meters of rock. According to a report released on Monday by the Institute for Science and International Security, the new centrifuges could produce enough 90 percent U-235 uranium for a warhead “in as little as two to three days” and enough for nine nuclear weapons in three weeks—or 19 by the end of the third month.